Instrumentation: solo piano, flute/piccolo, oboe, clarinet, bassoon, horn, trumpet, trombone, percussion (2 players), keyboard (w/preset tunings), 2 violins, viola, 2 cellos, bass

Tuner apps with tone generators needed for eight players.

First Performance: Ensemble Modern, Ueli Wiget (piano), Franck Ollu (conductor). January 6, 2020 (Kölner Philharmonie) and January 13, 2020 (Alte Oper Frankfurt).

Duration: 19 minutes

Commissioned by the Kölner Philharmonie as part of the Non Beethoven Project for the year 2020 and Ensemble Modern, in celebration of 40 years. Dedicated to Ueli Wiget and Ensemble Modern.

Commissioned by the Kölner Philharmonie as part of the Non Beethoven Project for the year 2020 and Ensemble Modern. Dedicated to Ueli Wiget and my friends in Ensemble Modern, in celebration of 40 years.

A line can go anywhere is a piano concerto in three movements, written with Ueli Wiget and my friends in Ensemble Modern very much in mind. They challenge you to be at your most inventive, since the commitment they bring is total and unequivocal. With Ueli, what I especially appreciate is his delineation of layer, precision, and boundless energy. I’d like to think those qualities translate into the piano writing.

There are multiple and contrasting ways of thinking about the role of the piano in this piece. As a heartbeat and engine, especially in the first and last movements, it can pull distant rotating objects into its orbit, while they continue to obey their own laws of gravity. This is especially relevant in the first movement, “Wound Wire,” where multiple simultaneous motors are being activated at once, and yet share enough rhythmic difference and harmonic coordination to function as a whole. The title of the movement alludes to the heavier, thicker strings on the piano – those in the lower register wound with copper wire – as well as the strong force of attacks that these strings withstand, and the inherent tension on and within piano strings that give the instrument its unique range of coloristic possibility.

The second movement, “Weightless/Suspended,” is a counterbalance, and yet related to the opening. Here, the focus is primarily on the role of the soloist, with multiple layers contained within the instrument, partitioned between several competing lyrical lines and supportive yet wholly disjunct outside layers. Throughout the piece, but especially in this movement, the sostenuto pedal provides a crucial role in balancing all the temporalities and personalities of the independent layers. The electronic keyboard also expands its role of playing shadow microtonal lines, incorporating a Rhodes piano sound tuned in just intonation to provide a dreamy, ethereal haze. And by the end of the movement, pure sine tones have taken over, with the soloist pushing up against their alien yet immovable frequencies.

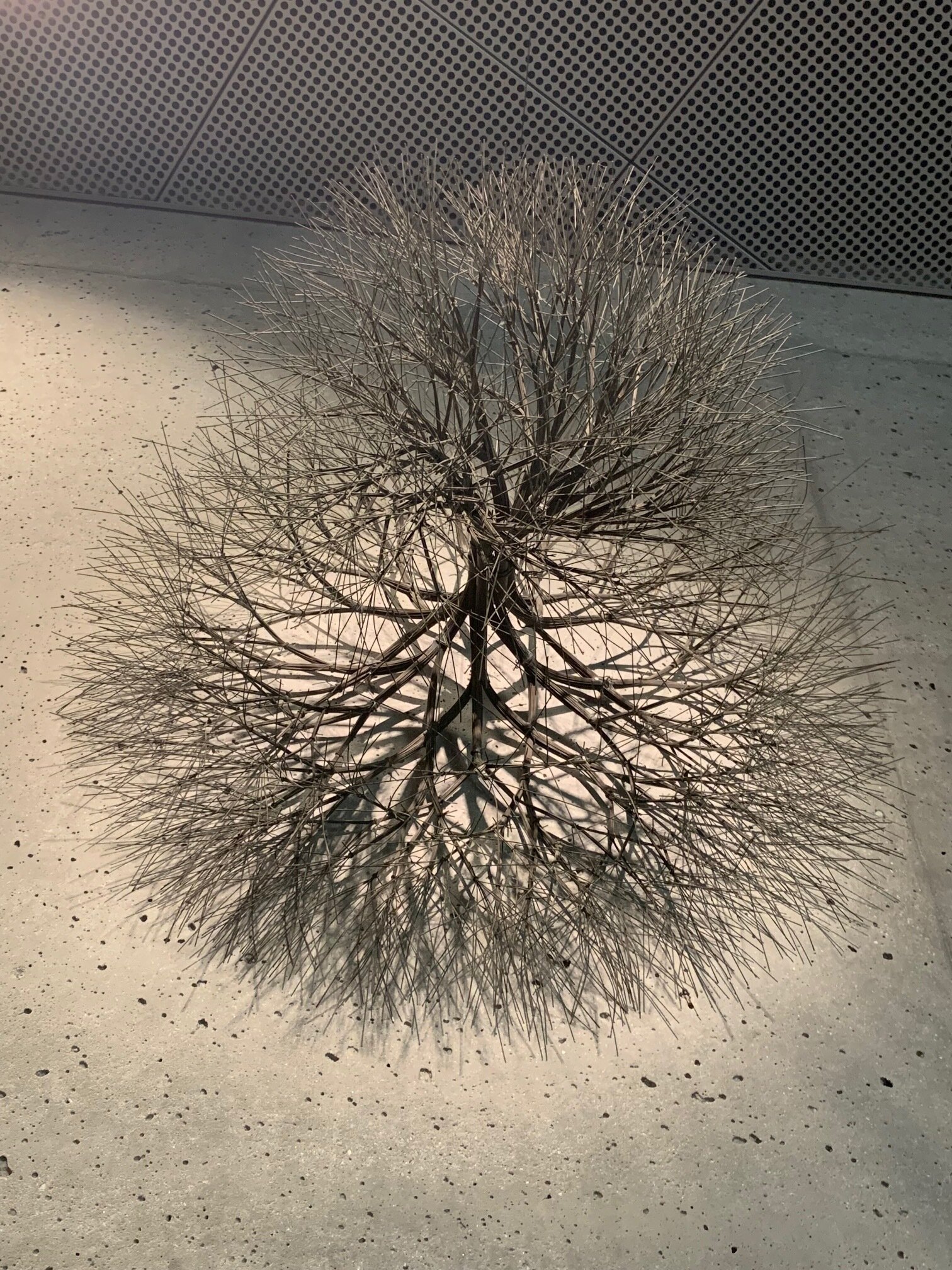

“Woven Wire – Homage to Ruth Asawa” opens with gradually changing patterns and loops, constantly shifting the focus of outer vs. inner melody and shapes within objects. Here I was inspired by the Japanese American sculptor Ruth Asawa (1926-2013), who was known especially in my hometown of San Francisco, where she spent her entire professional career. Her works from the 1950s and 60s use a technique of woven wire to create objects that might resemble baskets but more likely abstracted geometric shapes, often with symmetries and shapes-within-shapes that are multi-dimensional and especially rich when observed from multiple angles. Suspended from the ceiling in weightless space with a play of shadows on the walls, these works are so beautiful yet ultimately contradictory, with materials that are flexible and fragile yet dense and hard, and shapes that are buoyant but also made of edges. In other words, just like the piano itself, with its steel and copper wires enclosed in a box. The connective thread of the movement – its incessant motion, looped patterns, and lines-within-lines – ultimately derives from this aesthetic, which Asawa summed up perfectly: “I realized that if I was going to make these forms, which interlock and interweave, it can only be done with a line because a line can go anywhere.”

Anthony Cheung

“Alluding to the wire-mesh sculptures of artist Ruth Asawa, Cheung’s piano concerto A line can go anywhere explores the piano as a wired mechanical box. Slow microtonal descents are a recurring motif, staggered across instruments, and a just-intonation Rhodes keyboard adds colour. The first movement presents an opening cell gradually becoming more complex, like wire unfurling, the opening staccato and pizzicato flourishes eventually leading to dense microtonal textures. In the quieter second movement, dense passages transition to and from bare ones imperceptibly. In the thrilling third movement, a high piano trill motif is like a high-wire routine setting off a chain reaction of tremolo pyrotechnics throughout the ensemble, from rattling triangle to glissando violin.”

“San Francisco-born Anthony Cheung is one of America’s most imaginative young composers.…In the exquisite slow movement, “Weightless/Sustained,” Cheung exhibits a knack for synesthetic textures and colors. This is what a quartz might sound like if it could sing — the piano’s prismatic upper register supported by pizzicato strings and mallet percussion. Intricate metric layering and floating woodwind lines help to lend the impression that we’re astral-projecting through some crystal cosmos. The closing “Woven Wire” movement is an homage to the gyroscopic sculptures of Japanese American artist Ruth Asawa. Cheung captures the moiré patterns of her basket-like creations in a virtuosic perpetuum mobile for Wiget, who executes impossibly difficult cross rhythms with player-piano precision. For the pinwheeling grand finale, jackhammer repeated notes and funnel-shaped two-hand runs seem to suck us down into the accelerating vortex of Asawa’s crisscrossing wires.”

“Cheung’s concerto plays with the contrasts between occupied and empty spaces through the opposition between the piano and its orchestral accompaniment. The piano, as the sound surrogate for Asawa’s sculptures, throws out a filament of fragmentary, skittering lines whose interstices are filled by the surrounding strings, winds, and brass. In the first movement these latter tend toward independent, individual lines, while in the slow second movement they are grouped into fused masses. The agitated final movement suggests the experience of perceiving an object from shifting perspectives — an appropriate way to apprehend Asawa’s wire sculptures, whose elaborately traced shadows throw out dynamic patterns when seen from a mobile viewpoint.”